“ Life is about the moment you're in now”

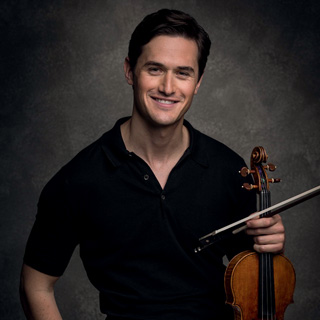

Violinist Charlie Siem on visual art, Instagram and future

|

Charlie Siem is well known in the world of classical music as one of

UK's most brilliant violinists. By the age of 33 he has performed with many of

the world’s finest orchestras and ensembles and released 4 CDs. Siem is also an

ambassador of The Prince’s Trust and a Visiting Professor at Leeds College of

Music (UK) and Nanjing University of Arts (China). Apart from that, he

collaborates as a model with fashion brands including Armani, Chanel, Dior, and

Hugo Boss.

— Let's start with the most recent

— I've been to Moscow a few times in the past, and today it's a completely different place. I was overwhelmed by how smart, polished, and beautiful the city is; it's so well maintained and slick. I spent only 3 or 4 days there, but I had time to walk around a bit. It was a pleasure to visit Moscow and of course to be part of this great festival, playing with Boris Andrianov and Julian Rachlin in the Vrubel Hall surrounded with incredible paintings. To me it's definitely an amazing memory that I will cherish. I really hope to come back to Russia, probably as a participant of the Vivarte festival again.

|

|

|

…I really hope to come back to Russia, probably as a participant of the Vivarte festival again… |

— The festival took place in Tretyakov Gallery’s Vrubel Hall. What do you think about the whole concept of mixing chamber music and visual art?

— Well, to me it's something quite striking.

Obviously, when you play an acoustic instrument — a violin — the space you play

it in is almost as important as the instrument itself. The sound that comes out

of the instrument is only as good as the walls that it resonates within. So

architecture is a crucial

|

|

Charlie Siem performing in Russia for the first time |

So when you play in the Vrubel Hall, it will make a slightly different performance, because you can't ignore these wonderful paintings. And when you engage with them, they change the way you interpret and perform the music — unless you're not sensitive to images at all.

— You were playing the Piano Quintet in G Minor by Shostakovich. Did it match the space it was performed in?

— It did, definitely. Like I said, you can make sense of any image with music. And I think the turbulence of the Shostakovich Quintet went very well with these bold majestic paintings of Vrubel.

— Was it a challenging performance for you?

— I think it must have been Boris Andrianov who programmed the Piano Quintet. And yes, it was a challenge, because it's a difficult piece and I didn't know it so well. And it was the first time I played it. But I'm a huge fan of Shostakovich.

— Really? Some people think his music is too complicated.

— No, I find that he's in many ways a very romantic composer. You know, there is a lot of torture, screaming sounds within the music, and it can be very painful, but there is also a lot of beauty. He had a lyrical sight and it's just stunning — the melodies Shostakovich wrote can be so heartbreaking and yet so amusing…

— Who is your favorite composer?

— I love Bach, to be honest. I'm also a huge fan of Brahms. There is actually a variety: Sibelius, Prokofiev, all kinds of wonderful composers.

— Do you listen to any modern music in your free time?

— Yes, I love listening to jazz, swing, rock music from the 70s. I could name Pink Floyd, David Bowie, some electronic music from today as well. I've got quite an eclectic taste, but of course I listen mostly to classical music.

|

|

…I think the turbulence of the Shostak ovich Quintet went very well with these bold majestic paintings of Vrubel… |

— One of your thre e sisters, Sasha, is a professional music writer. Do you often collaborate with her?

— Not much. We've done a few things together, and it was nice because she's my sister, I love her, we have fun together. Besides that, she's a great artist, she's always changing but still has a lot of integrity. And she also has a very specific idea of how she writes music and how she likes to express herself. I admire her a lot.

— You composed and recorded your first work “Canopy” 5 years ago. Why did you decide to try yourself as a composer?

— I was commissioned by a friend of mine, actually. He worked for CBS at that time and he needed a piece written for his project. So I said, “Look, I'll take it on, I'll try it. It's a challenge for me, it's something different to do.” And it was a wonderful experience to be in front of the orchestra interpreting a completely new piece that I conceived of. It was a totally different perspective, because the idea I had in my head was not necessarily what it sounded like with the orchestra. So we worked on it a lot and the whole process was quite rewarding. The idea came very quickly but it took about a month to orchestrate it.

— Have you written anything else since then?

— No, but sometimes I compose on a piano; I like coming up with my own musical ideas. I haven't written anything down yet, but hopefully I will.

|

|

|

With Boris Andrianov, Art Director of the Vivarte festival, on the stage of the Vrubel Hall |

— Where do you see yourself 20 years from now?

— I can't tell you. I'm not somebody who plans much for the future. I try to do the best that I can with what I have now, and that's it. I don't think in terms of what is/was the greatest moment of my life, I just feel like life is about the moment you're in now, about what are you working on now. What's happened before or might happen later is like mythology or fantasy. I just think what I'm focusing on or where I'm directing my intention now is what's important. Like when I wake up and practice and I think, “This is where I am now with the violin, this is what I'm working towards,” that must be the highlight.

— So what are you working on now?

— Right now there are not many concerts in my schedule, which is rarely the case. It's a nice opportunity to go back in my repertoire, so I'm looking back over the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto which I've performed a few times. It's an important piece for me, I need time to work on it, to think about it.

— Your next concert is in September, in Bærum Kulturhus, Norway. When will you start to rehearse?

— Well, I'll start in September. I haven't chosen the program yet, I need to decide what I will play.

|

— There is a variety, for nowadays people discover classical music through TV, YouTube, etc. So you see people with all kinds of background: they can be young or old, wealthy or not. I think it's very exiting. Maybe in the past there was a prejudice about the audience of classical music, but not today.

— A lot of articles including the Wikipedia page describe you in the following way: “an English contemporary classical violinist as well as a model.” Does this “as well as a model” bother you?

— People can interpret who I am or what I do in any way they like. It's beyond my control, I just do what I do and that's it.

— Do you read what people say about you in the Internet?

— Not intentionally. It's not something I look out for. I'm trying not to let it affect me.

— Classical music and high fashion are almost opposite areas. Does your Instagram profile somehow make people take you less seriously?

— The image media provides to people is always an illusion. As for me, I post things if I feel like posting them. And if somebody has a bad impression of me they will find some imperfection in me whatever I do — that's life. You can't control what people think, so one shouldn't care too much about impressing others. It’s a waste of energy.

— “A modern man,” the documentary about you, was made two years ago. Did it change anything in your life?

|

|

Charlie Siem plays the Guarneri del Gesù violin (1735), known as the ‘D’Egville’ |

— I didn't think it was so good; it made me seem very depressed and it wasn't that accurate. I don't have a strong feeling against it, but didn't like it a lot either. It was a little bit boring.

— What would you change to make it more accurate?

— It should have been more focused on what I do — the music itself, the process that I go through to build up a performance in a psychological and a technical sense. Instead, it was more of a cliché about a young guy who has lots of stuff and is still searching for happiness. And even this existential theme wasn't exploited in a complex and interesting way, it was a bit simple.

— Я не исключаю, что однажды сменю сферу деятельности, но пока не было дня, чтобы я пожалел о своем выборе.

— Your biography says you play “the 1735 Guarneri del Gesù violin, known as the ‘D’Egville’.” Why is it so important that the instrument should be old? People don't usually say anything like that about guitars or drums.

— The guitars are made differently now compared with those days. And they were not necessarily as well made in the early 18th century. Whereas the violin has not changed at all since that period, and the best makers were from that time; they didn't get any better afterwards. So we cherish and value these masterpieces of Guarneri and Stradivari. You can make a guitar in the 21st century that will sound better than one from the 18th century, but it's not the same with the violin. They sound fantastic once they're 300 years old.

— Have you ever considered changing your profession?

— Maybe I'll change my direction, but I don't have doubts about what I've done so far. Maybe tomorrow I'll wake up and do something else.

Text: Elena Kovyleva

The Museum of Private Collections as part of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts was established in 1985 thanks to Antonova and the collector Ilya Zilberstein, and the museum’s holdings have been compiled with her direct participation.

Back