Connoisseurs extraordinaire

Irina Antonova, President of the A. Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, devoted her entire life to the museum and its collection

|

Irina Alexandrovna’s experience is unique: 72 years in a museum and 52 of them as its director. It would take more than one page to recount all Antonova’s achievements, titles, and awards. But since the subject of our conversation is art collections and art collecting traditions in Russia, we can mention just one line from the long list: the Museum of Private Collections as part of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts was established in 1985 thanks to Antonova and the collector Ilya Zilberstein, and the museum’s holdings have been compiled with her direct participation. Antonova actively supports the idea of recreating the Museum of New Western Art in Moscow based on the reunification of Sergey Shchukin’s and Ivan Morozov’s collections, currently divided between the Hermitage and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.

— You said once in another interview that

the craft of collecting in Russia in the 19th — early 20th century was of a

special nature. One often hears that the question of how Shchukin and Morozov

managed to amass such stunning collections remains puzzling even for

researchers. Of course,

— Collectors have always existed, I suppose. What makes a collector? The passion for fine art, the desire to possess it, and the act of making a choice. A collector can choose — the whole world lies in front of him or her… Why did Sergey Ivanovich Shchukin and Ivan Abramovich Morozov become the first individuals to acquire the works of their contemporaries, the French artists who at the time were not understood in France? Take the painter Caillebotte, the author of the famous Floor Scrapers. He once offered to donate his excellent collection of impressionists to the Louvre. And the Louvre refused. The collection ended up somewhere else and only after a time finally arrived in the D'Orsay Museum.

|

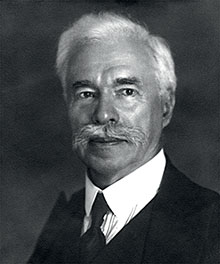

Sergey Ivanovich Shchukin |

Now, even at that time two our Russian merchants were able to understand the

impressionists

— How did they manage to have so subtle an art sense?

— Well, how such things are possible? They were gifted with brilliant perception and vision. They had some premonition of coming changes, not unlike great artists and poets, or the animals who feel earthquakes before others do.

— So was this an instinct of sorts??

— An instinct, as well as some very special quality. I am not sure what is the right word for it, but it’s a certain way to perceive the world one lives in. These people, who were neither poets nor revolutionaries, for some reason were drawn to impressionism. So, okay, why wouldn’t they be content with purchasing Boucher or Ingres, or Delacroix, or Edouard Manet even? But they wouldn’t — instead, they started buying Gauguin, Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse. And the way they did it — actually very consciously!

Do you know the story of Dance and Music by Matisse? Sergey

Ivanovich (Shchukin) commissions these paintings. Alright, the order is placed,

the collector comes to Moscow, and then he thinks to himself, «No, this is not

it.» So he should cancel, right? Wrong. He feels ashamed and writes to Matisse

again, «Send them.» Why does he still appreciate Dance and Music? Just think

about it, we are talking the early 20th century! The Silver Age,

There is nothing more difficult than to see the art of one’s own times for what it is. Later, when things are settled — yes, that’s a different story. Say, if you have a good eye, you can tell a genuine item from a fake (at least from a crude fake, a crude copy). But these people were able to see something that had never happened before. That’s priceless! That’s why they were extraordinary. And that’s why I am fighting and will fight for the restoration of the Museum of New Western Art — a museum that was once established based on the Shchukin and Morozov collections.

|

Valentin Serov. Portrait of Ivan Abramovich Morozov |

I must say that Tretyakov amazed and inspired everyone. After all, what he did was incredible — he gathered the entire Russian school art. And who else had been gathering it? No one valued it. Vyazemsky and others collectors kept gathering mostly the West. And suddenly, Tretyakov starts buying, enthusiastically, paintings by Russian artists, seeing some future in them… Although nowadays many people say, «Well, what was he collecting there, all those Itinerants?» Yes, he bought up works of the Itinerants, but not only. The way I see it, Tretyakov had been collecting works of the school that had special ideas, a special relationship with nature, and later these ideas would take their place in the art of the future.

— And what about today? Can we imagine some collective portrait of a modern Russian connoisseur and art patron?

— Today, finally, private collectors are no longer viewed as some kind of brigands. Of course, those who focus on buying and selling do exist, but a real collector (who also buys and sells) is an art connoisseur first and foremost.

— Without having a passion for art, it’s probably impossible to be a collector.

— Yes, it is impossible. Although only precious few are able to discover new areas. What Shchukin and Morozov saw was unprecedented.

— Yes, they were pioneers, unafraid to take risks…

— For instance, the Manasherovs purchase very interesting items, not at all trivial. And then they introduce these items into the circuit, to be recognized. They have the sense of it, this deep understanding of the development of art. But most others buy only already acclaimed works, without making special discoveries. They wouldn’t buy something so later they’d suffer like Shchukin — did I buy a true thing of art or not? And Shchukin didn’t have these doubts because of the money, not at all. What was important for him was whether or not he was right about the quality of the work, the artist’s talent. After all, Shchukin purchased works no one else in Russia was ready to buy, except Morozov. No one else understood. And both these geniuses were born in Moscow.

— It seems to me that the very identity of the collector is interesting. Sometimes the story of a painting, the way it came into the collection and what happened after, is more interesting to the viewer than the work itself.

— Yes, I must tell you, I would even create a collectors' museum. It would start with Peter the Great and his Kunstkamera, etc.

|

…I think the Museum of Personal Collections is the right place to introduce a personality, to tell the story about the way the craft of collecting evolved in general and took shape in Russia… « |

— Do you want to create a new independent museum? Or is this idea related to revamping the Personal Collections Department?

— Yes, the Museum of Personal Collections. There is a

certain ratio for all existing collections. Collectors here are

The Museum of Personal Collections has some our

contemporaries as well, like Eduard Steinberg. In the contemporary art section,

we could also show Tyshler. By the way, in the West they know him very well —

for example, in Belgium. There is a large collection of Tyshler's paintings

there. And if we had a contemporary art section in the main exposition, we

would receive more works from abroad: they would know that we had a dedicated

section and not just some individual exhibitions, so they would definitely give

things away. I’d suggest

— So, completely redo the concept?

— Yes, that's the idea. Keep all the current

collectors and continue to represent everyone who will donate items. Although

not every private collection we have is a donated one — some were simply

nationalized. But then again,

It can be displayed as part of the main exhibition but should be also shown at the Museum of Personal Collections. Why not? I think the Museum of Personal Collections is the right place to introduce a personality, to tell the story about the way the craft of collecting evolved in general and took shape in Russia.

We have got a lot of stuff from St. Petersburg. These funds,

The definition of „collecting“ must be expanded. We have to include in it the centermost detail, the collector's figure itself, not just what has been collected. And we will have an exciting story in the end — the story of how the collection had been gathered, and why some collected those while others collected these… In my opinion, all this should be totally fascinating to show.

|

…these Sergey Shchukin’s words have reached us— he wrote to Tsvetaev, „I gather my collection for Moscow.“ |

— And then the collectors gathering contemporary art, the art of the second half of the 20th and 21st centuries, will also have a desire to donate to the museum?

— How not?! Is it really bad for them to be represented after Matisse and Picasso? Why not? After Salvador Dali… We have graphics there and so on. This way we will make it appealing. It’s a way to get into the mainstream, as they say.

— Yes, it will be interesting to find out who they are, these people who have been collecting art, what motivates them, and what the collectors of different eras have been interested in.

— Yes. And most importantly, we have the material. Among others, there are items that the state acquired for money after the revolution. All this must be shown — who donated what and whatever was nation alized, how the collections had been put together.

This will be the story of the existence of the entire body

of art works in the country, shown at least in one Moscow museum… And after the

[Second World] war, we are talking

— So the plan is to show the history of art in the main part of the museum, the way it is now, and use the Museum of Personal Collections for displays related to the history of collecting?

— Yes, exactly. Here are the paintings, and there are the people who were interested in them, who loved them. It’s going to be a special museum. I would do that. We have so many items in storage! And ultimately there are collectors behind each one — individuals who love art and devote their time and life to it.

Interview by Olga Muromtseva

Back