23 December 2016

Pirosmani and Co.

For the first time at the

Pushkin Museum: Georgian painters of the first third of the 20th

century

Text: Olga

Muromtseva

|

Niko Pirosmani (Niko

Pirosmanashvili).

Prince with a Horn of Wine. 1909

|

This fall-winter exhibition

season in Moscow museums has seen a grand assortment of vibrant art events.

Long queues cannot frighten art lovers keen to view the masterpieces of the

Vatican collection or visiting displays from French and Italian museums. Going

to an art show has become a fashionable trend, and its followers closely

monitor museum programs for updates, booking tickets in advance. The U-ART

fund, jointly with the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, has created a project

that in the list of the winter 2016/17 exhibitions is worthy of a prominent

spot — thanks to the concept behind it.

The exhibition «Georgian avant-garde of

1900−1930s: Pirosmani, Gudiashvili, Kakabadze, and others. From museums and

private collections» is open to the public from 8 December 2016 to 12 March

2017.

For the first time in the modern Russian

history, works of the most prominent Georgian avant-garde artists of the first

third of the 20th century have been brought together at one exhibition. The

three floors of the Private Collections Department of the Pushkin Museum host

the display of paintings and drawings by Niko Pirosmani, Lado Gudiashvili,

David Kakabadze, Kirill (Cyril) Zdanevich, Petre Otskheli, Zygmunt (Zygi)

Waliszewski, Irakli Gamrekeli, and others. The exhibition also includes the

artists' lifetime prints, cinema posters, theatrical costumes, archive items,

and movies.

Major Russian museums, including the

Tretyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum, the State Museum of Oriental Art, the

Bakhrushin Central Theater Museum, as well as private collectors from Russia

and Georgia, have been invited to participate in the event. By gathering

artwork from multiple museums and private sources, the curators Iveta

Manasherova and Elena Kamenskaya have managed to create a one-of-a-kind display

featuring more than 20 pieces by Niko Pirosmani (Pirosmanashvili), each

boasting an impeccable provenance and fascinating history.

A million legends and the truth of

art

|

|

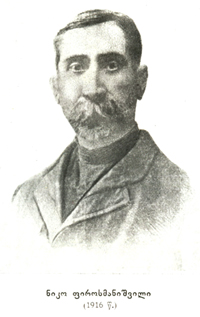

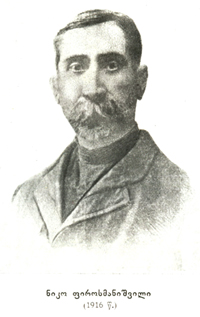

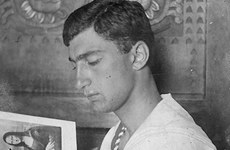

Niko Pirosmanashvili.

Photograph. 1916

|

In 1912 Mikhail Le Dentu and Ilya Zdanevich

during a trip to Georgia discovered a self-taught painter named Niko Pirosmani,

whose art was in tune with the most daring artistic ideas of the era and

reminiscent of Henri Rousseau's primitivism. For Georgian artists of the «new»

generation, Pirosmani's paintings were an example of pure art free of academic

staleness. Pirosmani's works, for the first time displayed in Russia in 1913 at

the Mishen' exhibition, made a huge impression on Russian avant-garde artists.

Pirosmani's influence can be felt in Mikhail Larionov's and Natalia

Goncharova's primitivist paintings.

In Russia, Pirosmani's works enjoy

affectionate appreciation; tales associated with his life and art are

well-known. The poor artist's romantic attraction to actress Margarita has

become part of the Pirosmani mythos and made the plot of the popular song

«Million red roses.» To this day, most stories about the artist's life have no

hard documentary evidence. «Niko Pirosmani has so completely dissolved in the

common folk that it is difficult for our generation to discern the facts of his

personal life. His everyday life was so mysterious that, perhaps, he will have

to remain without a conventional biography…» Written in 1926, these words

still make sense today.

The exhibition «Georgian avant-garde …»

provides a rare opportunity to see all Niko Pirosmani's masterpieces in one

place: his famous feast scenes («Family Company», TG, «Tiflis Shopkeepers

Dining with Phonograph,» Shalva Breus' collection, Moscow), animal figures

(«Roe Deer», Valentin Schuster's collection, St. Petersburg, «Tatar — Camel

Driver», Igor Sanovich's collection, Moscow), human portraits («Portrait of

Ilya Zdanevich», Valentin Schuster's collection, St. Petersburg, «Prince with a

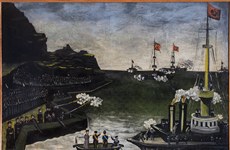

Horn of Wine», RM), and historical paintings («Naval battle. Russo-Japanese

War»). These powerful works carry the viewer into the world created by the

artist, depicting the real and imaginary life of the early 20th century

Georgian towns and villages, folk traditions, characters, architecture, ways of

living, and national culture.

Georgian modernists in

Paris

For two of the other artists whose paintings are featured at

the exhibition - Lado Gudiashvili and David Kakabadze — Pirosmani's work

was an object of unflagging interest. Gudiashvili met Pirosmani in 1915, and

this encounter undoubtedly had an impact on the younger artist. Not unlike

Pirosmani's, his works also relate the atmosphere of Georgian life, its rhythm

and flavor. However, Gudiashvili's style, formed by the culture of his native

land as well as by Persian miniatures and later refined during his five-year

stay in Paris, is distinctly elegant and sophisticated. In Paris Gudiashvili

quickly plunged into the maelstrom of artistic life, meeting and befriending

the likes of Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger, and other artists

of the circle known today as the Paris School. Gudiashvili's art displayed at

the Salon d'Automne enjoyed success, which brought him more friends as well as

lovers of his talent, happy to acquire his paintings.

|

Lado Gudiashvili. Green

fairies. 1925

|

As the Paris period is considered the most remarkable and

original in Gudiashvili's oeuvre, it is no wonder most works presented at the

exhibition in the Pushkin belong to this time in his career. This is how the

famous art critic Maurice Raynal, the author of the first monograph on Lado

Gudiashvili published in 1925 in Paris, describes his work: «Being embodied in

the exclusively national spirit, it [the art] presents to us the scenes of

everyday Georgian life. Women and warriors with strikingly shaped eyes — true

children of a nation lively, belligerent, drunk with their outdoors lifestyle,

mountainous expanses, fast horseback riding, and all sorts of adventures. Here

they are fighting, here having a riotous feast, here they are dancing, here

seeking comfort in love, and almost all of it, so to speak, — on horseback, for

the horse in the life of a Georgian plays the most significant role.»

Gudiashvili's paintings are truly poetic and full of

symbols. Themes and characters depicted by the artist reflect his singular

talent and the unending homesickness that haunted him even in the happiest and

most successful Parisian years. In 1925 Gudiashvili decided to return to

Georgia, despite the diverse perspectives the art world of Paris opened

to him.

Innovations of David

Kakabadze

|

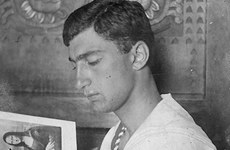

Georgian artists in Paris. Left to

right:

T. Piralishvili, L. Gudiashvili, D. Kakabadze, E. Akhvlediani.

1925

|

Like his friends Lado Gudiashvili and Shalva Kikodze, David

Kakabadze received a grant from the Georgian Artist Society and, together with

Gudiashvili, arrived in Paris on January 1, 1920. Both artists instantly fell

in love with the city and often roamed the squares and streets of Paris, making

pencil sketches, but their styles were decidedly different. Lado's thin, broken

lines starkly contrasted with David's vibrant strokes. Both drew inspiration

from Georgia, but Kakabadze's works testify to the fact that he was fascinated

with his homeland's nature first and foremost. He was also enthralled by the

architecture of ancient Georgian churches, especially the complex stone relief

patterns decorating their walls. Kakabadze studied these ornaments specifically

and even wrote an entire paper on the subject complete with his sketches.

Except for a few early items done in the realist manner, the

exhibition presents mainly abstract works by David Kakabadze, created during

his Paris period. The artist's transition to abstraction can be observed in the

watercolor set entitled «Brittany». It was this north-western province of

France, visited by Kakabadze in 1921, where he created first realist, then

cubist, and finally biomorphic images of Breton houses and boats on water.

David Kakabadze was an experimental artist and researcher.

Having studied engineering at the Natural Sciences Department of St. Petersburg

University), he loved to tinker with mechanical devices. In 1922, he created a

stereo movie projector that enabled the audience to see three-dimensional

images without glasses. Kakabadze patented this invention in many countries —

France, USA, Great Britain, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Belgium, Italy, Hungary,

and others — and a stock company was founded to fund the construction of a

working prototype. Kakabadze was able to build the prototype and get first 3D

images, but subsequent lack of funds prevented him from working further on the

invention. Later, drawing on this experience, the artist created his collages

or, as they were named afterward, constructive-decorative compositions, which

may be considered his special legacy in visual arts. The materials he used were

wood, metal parts, lenses, mirrors, and other items left over from his

inventions. The images created in this manner were closer to organic, embryonic

shapes. Kakabadze was one of the first to use spray paint for coloring the

background. He also devised special frames, wooden and metal, adorned with

various spare parts, to be integral components of the compositions.

|

David Kakabadze (left) and Shalva Kikodze

in Paris.1924

|

The art of David Kakabadze is not as well-known to the

Russian public as it deserves. Most of his works presented at the exhibition

come from private collections. Kakabadze's only work from the Tretyakov Gallery

collection was donated to George Costakis Museum. It is noteworthy that

avant-garde collectors have always valued Kakabadze's works highly. The US

artist, collector, and art critic Katherine Dreier, who has done much to

popularize avant-garde art in the United States, acquired an abstract sculpture

by Kakabadze and several of his watercolors in the mid-1920s. Thus the

Georgian's art appeared at the Brooklyn International Exhibition in New York in

1926 and later ended up in the collection of the Yale University Art Gallery,

to which Dreier donated a treasure trove of modern art.

Upon their return to the homeland, the lives

of David Kakabadze and Lado Gudiashvili followed different paths. However, both

artists had worked in theater and cinema. Together they acted as production

designers of a black-and-white silent film «Saba». Gudiashvili also

participated in the production of the films «Khabarda», «Doomed», «The

Divorce», and others. The undoubted masterpiece of David Kakabadze as a film

art director was the documentary «Salt of Svaneti.» Fragments of these and

other Georgian motion pictures of 1920−30s are shown at the

exhibition.

Theater

|

Brothers

Kirill and Ilya Zdanevich hold the honor of discovering the work of Niko

Pirosmani to the artistic

community

|

A special part of the exhibition displays theatrical works

of Georgian artists. The transformation that Georgian theater underwent after

the Russian Revolution was accomplished owing mostly to the efforts of

directors Kote Marjanishvili (1872−1933) and Sandro Akhmeteli (1886−1937). The

experienced Marjanishvili, having taken the helm at the Tbilisi Shota Rustaveli

Theater, found gifted young artists Irakli Gamrekeli and Petre Otskheli, whose

early 1920s works constituted a breakthrough comparable to the one the

constructivists made in the Russian theater. The production of Vladimir

Mayakovsky's «Mystery-Bouffe», in the end abandoned, became the first

experiment, and the visual arts part was entrusted to Gamrekeli.

|

Kirill Zdanevich. Suprematist set

design. 1925

|

Theatrical drawings by P. Otskheli, I. Gamrekeli, and K.

Zdanevich — bright, unusual, futuristic — introduce the exhibition visitors to

the creative atmosphere of Tiflis of the 1920−30s, with its indispensable

ingredient — the famous artistic cafés «Himerioni», «The Argonauts' Ship», and

«Peacock's Tail». The walls of these remarkable establishments were painted by

the likes of Gudiashvili, Kakabadze, Sudeikin, and Toidze. They were frequented

by Georgian poets, writers, artists, and philosophers, as well as their Russian

counterparts who fled from the famine and revolutionary turmoil to the warm and

welcoming Tiflis (capital of Georgia, Tbilisi after 1936). Within their walls

were born the poems and plays later published by the famous group 41 Degrees

founded by Terentyev, Kruchenykh, and Ilya Zdanevich. Some of these

publications are also displayed at the exhibition, complementing the diverse

and vibrant panorama of the artistic life in Tiflis during the first third of

the 20th century.

In total, the exhibition «Georgian Avant-garde» features

more than 200 paintings and drawings as well as a printed publication, which

includes a series of scholarly articles written by an international team of

authors, the catalog, and the art album section. Illustrations and catalog

materials have been provided in part by museums of Georgia, which responded

enthusiastically to the organizers' inquiry. The exhibition of Georgian

avant-garde in the Pushkin Museum is an international project that aims to

emphasize the importance of dialogue between the two countries the histories

and cultures of which have been inextricably linked for many centuries.

Niko Pirosmani (Pirosmanashvili). Family Feast. 1906

|

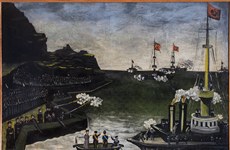

Niko Pirosmani (Pirosmanashvili). Niko Pirosmani (Pirosmanashvili). Naval battle. Russo-Japanese War. 1906

|

Niko Pirosmani (Pirosmanashvili). Sister and brother (according to the play by V. Gunia)

|

Lado Gudiashvili. Horses. 1921

|

David Kakabadze. Abstract composition. 1921

|

David Kakabadze. Constructive-decorative composition. 1925

|

Lado Gudiashvili. After the feast. 1922

|

The girl and the goose with goslings. 1917

|

Karachoheli (noble) with a horn of wine

|

Kirill Zdanevich. Sketch of a Spanish costume. 1910

|

Irakli Gamrekeli. Sketch of a set design for the play "Lamara". 1930

|

Irakli Gamrekeli. Set design sketch for the play "Mystery-Bouffe". 1924

|

Ilya Zdanevich

|

Portrait of Kirill Zdanevich by Zygmunt Waliszewski

|

David Kakabadze (left) and Shalva Kikodze in Paris. 1920

|

26 December 2016

Russian media did not ignore the international cello festival — virtually every concert of the program provoked the interest of journalists, and the artistic director and guests of the festival became the heroes of many publications. Let's summarize the reviews.

8 December 2016

A private view of Georgian art at the Pushkin Museum. The entire business and cultural elite of Moscow gathered that evening at the Private Collections Department of the Pushkin Museum, the three floors of which were milling with notable guests.

7 December 2016

At the Vivacello festival, the Italian cellist and composer performed his Antidotum Tarantulae XXI concert for the first time in Russia. This “modern antidote for tarantula bite” stirred, probably, most discussions in the press and among the festival visitors alike. The expressive modern music is in conversation with the past, with the Renaissance and Baroque — and for explanations we turned to Giovanni Sollima himself

29 November 2016

The 8th VIVACELLO Festival, held as usual at various Moscow venues under the management of Boris Andrianov and the culture and charity foundation U-Art: You and Art, has exposed certain important issues concerning interpretation and perception of music written for so unhurried an instrument. (Osip Mandelstam likened the density of the cello timbre to honey flowing from a tilted glass jar)

2 November 2016

Art Patrons Iveta and Tamaz Manasherov Participate in a Pompidou Center’s Project. The collection of Russian art in the P ompidou Center is well-known internationally and includes works by Kandinsky and Malevich,

Chagall and Pevzner, Puni and Exter, Bulatov and Kabakov - great names and seminal works all throughout ...

Back