Mikhail Muginshtein: Opera is a passionate lady

Text: Arina Soboleva

Photo: Sergey Karpov

Opera is like a women. Full of life, restive, she always

has to be accompanied by her counterpart, the stage play. This is the opinion

of the musicologist, opera historian, critic, and and Merited Worker of Arts of

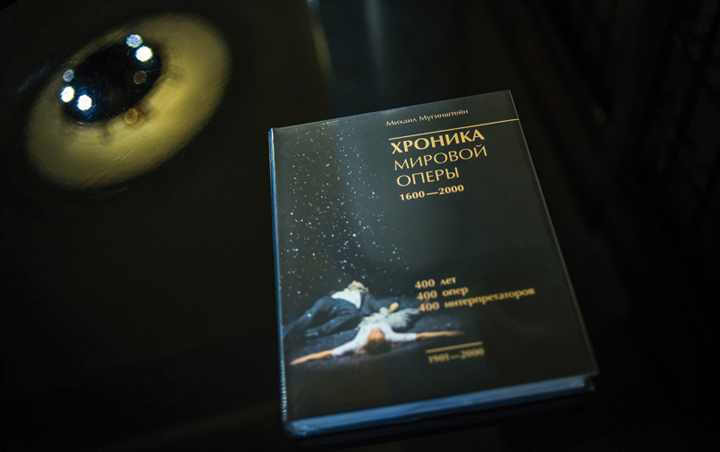

Russia Mikhail Muginshtein. In April he presented the third volume of the

encyclopedia “World opera Chronicles”, which was published with the support

of the cultural charity

An avant-garde art

|

— Yes, some people think that opera is an old lady from the

coffer, or, at best, her shoes that are back in style. In reality, opera is a

passionate lover, and that’s how people have been viewing it from beginning. As

the coolest

— Nowadays we often hear — as though it’s in the spirit of our times — that opera has had its days. Over and done with.

— The notion that opera is dead is utter nonsense. New works

appear every year. For example, the Stanislavsky Electrotheater runs “The

Sverlitsy” series created by Boris Yukhananov. This is a peculiar fantastical

show, and a whole group

— What do you mean?

— I am convinced that the language of contemporary opera shouldn’t be totally disconnected from the classical origin. Obviously, I don’t mean writing melodies in Glinka’s style. But we should keep the genetic link with the predecessors. Otherwise we might witness something described in Hamlet: “The time is out of joint.”

The famous Russian semiotician [Mikhail] Bakhtin coined the term “genre memory”, and contemporary opera should keep this memory. But besides the “genre memory” there is the “genre outfit”, which changes from one historical age to another. Imagine a modern youth who looks totally different from her family predecessors, sticks to the unisex style, and wears those dreadful platform sneakers. However, she keeps the family traits of her grand-grand-grandmother.

— So what is the outfit of contemporary opera?

— You see, “contemporary opera” is a very relative notion. There are works created by contemporary composers, and then there are new interpretations. These are two different things. If you want to talk about contemporary literature, you won’t discuss Pushkin and Gogol, you will be interested in [Vladimir] Sorokin and [Viktor] Pelevin. In opera, however, one may also talk about a new staging of a classical work.

|

Gershwin’s opera “Porgy and Bess” staged at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, November 2014 |

You can treat any classical opera as a contemporary one. For example, Andrey Zholdack staged “Eugene Onegin” at the Mikhailovsky Theater and two years ago was awarded the Golden Mask. This is a very peculiar thing. He takes Tchaikovsky and creates his story based on his music. This story is brilliantly imaginative at times, but it trespasses brutally on Tchaikovsky’s story, up to changing the musical score.

If Tchaikovsky takes Pushkin’s Onegin, he also creates a

totally different Onegin – we don’t have any doubts about that. This is quite

natural. Any work of art is not unlike a museum. When you enter a museum,

— It is hard to refrain from asking you here about your take on the Tannhauser scandal.

— When I analyzed this infamous play by Timofey Kulyabin, I was troubled by the fact that for some reason this creative issue became a political one. From one side, the opera was discussed by conservatives, who traditionally like to keep lid on the matter, from the other, by liberals, who like to rebel without looking at the matter. And the matter here is that the director created a story which at certain points disagrees with the music creator. Is this a contemporary opera? Yes. But how does it attain this contemporary quality? By developing a dialogue with the author? No, by peddling its story. I am more of an advocate of a subtle and deep, top to bottom exploration of the author’s artistic universe, of the artwork, and of discovering new mazes in it.

The fabulous five

— Do you think that the things which happen today on Russia’s opera stage go beyond it?

— Yes, both our composers and performers are in demand worldwide.

|

Anna Netrebko and Mariusz Kwiecien in “Eugene Onegin” on the stage of Metropolitan Opera |

— Russian classical opera is not as popular as the Italian, the French or the German one. We need to understand this. If “Eugene Onegin” is staged worldwide, this doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the Russian opera. Actually, there are several Russian titles that do quite well globally. “Eugene Onegin” is at the top of the list, followed by “Boris Godunov”, “The Queen of Spades”, “Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District” by Shostakovich, “The Love for Three Oranges” by Prokofiev, and, last but not least, Mussorgsky’s “Khovanshchina”. Essentially, if we were to speak of national operatic schools, Russian opera ranks fifth in the world, since the Czechs are also ahead of us.

— This is a surprise.

— People in Russia simply don’t know about it. The operas of Leos Janacek, for example, are played more often than all Russian productions taken together. However, there are only five opera schools in the world. We cannot speak about an English opera school, as there are only two composers, which cannot be regarded as a national school. One can’t speak of Polish, Hungarian, or other schools. So ranking fifth is actually an honor.

|

Actually, there are several Russian titles that do quite well globally. “Eugene Onegin” is at the top of the list

|

— It just so happens that Russian audience is more inclined

to attend a ballet performance than opera. In the West, however, the situation

is different. In Germany, Austria, Italy you will never find more than two

ballet performances

400 years, 400 operas

— Let’s change the subject to your book. Why a new opera encyclopedia? To be sure, many had attempted such a fundamental study before…

— “Many” is a huge overstatement. I can say that my

encyclopedia is the first one of its kind in Russia. And our country’s

circumstances, especially those concerning the economy, don’t give any

guarantees of continuation. So my first encyclopedia may become the last one.

— Your encyclopedia is an authorial one. What does this mean exactly in relation to your “Chronicles”?

— The most important and precious section in the

encyclopedia for me is the commentary,

|

The third volume of the book covers the whole 20th century |

— The span is vast, fantastic!

— Yes. But never mind the six hundred pages. The three

volumes weigh six kilos, now that’s worth something! (Laughs.) In truth, I can

say this effort was needed.

— The first volume was released in 2005. How much time did the project require?

— Twenty years. But in reality I have been working with opera since my university studies. I can tell precisely — it began with a term paper during my fourth year in the conservatory.

— In Russia your encyclopedia became one of its kind. What about other countries?

— In this respect the leader is Germany, with more than a

dozen reference publications. I must say German encyclopedias are more on the

technological side of things. They typically feature elaborate work on details

but are somewhat lacking in the artistic, culturological approach. Art studies

itself is a centaur,

Back